Balikbayan

An sculpture and photo exhibition proposal and general note page that re-imagines the balikbayan box as a surreptitious museum plinth, undoing the plinth’s traditional purpose as a stable technology of outward display and presentation into an alternative: a sealed vessel capable of safely hiding, protecting, and spiriting away objects and images back to the Philippine Islands.

First sketches for exhibition proposal, 2019

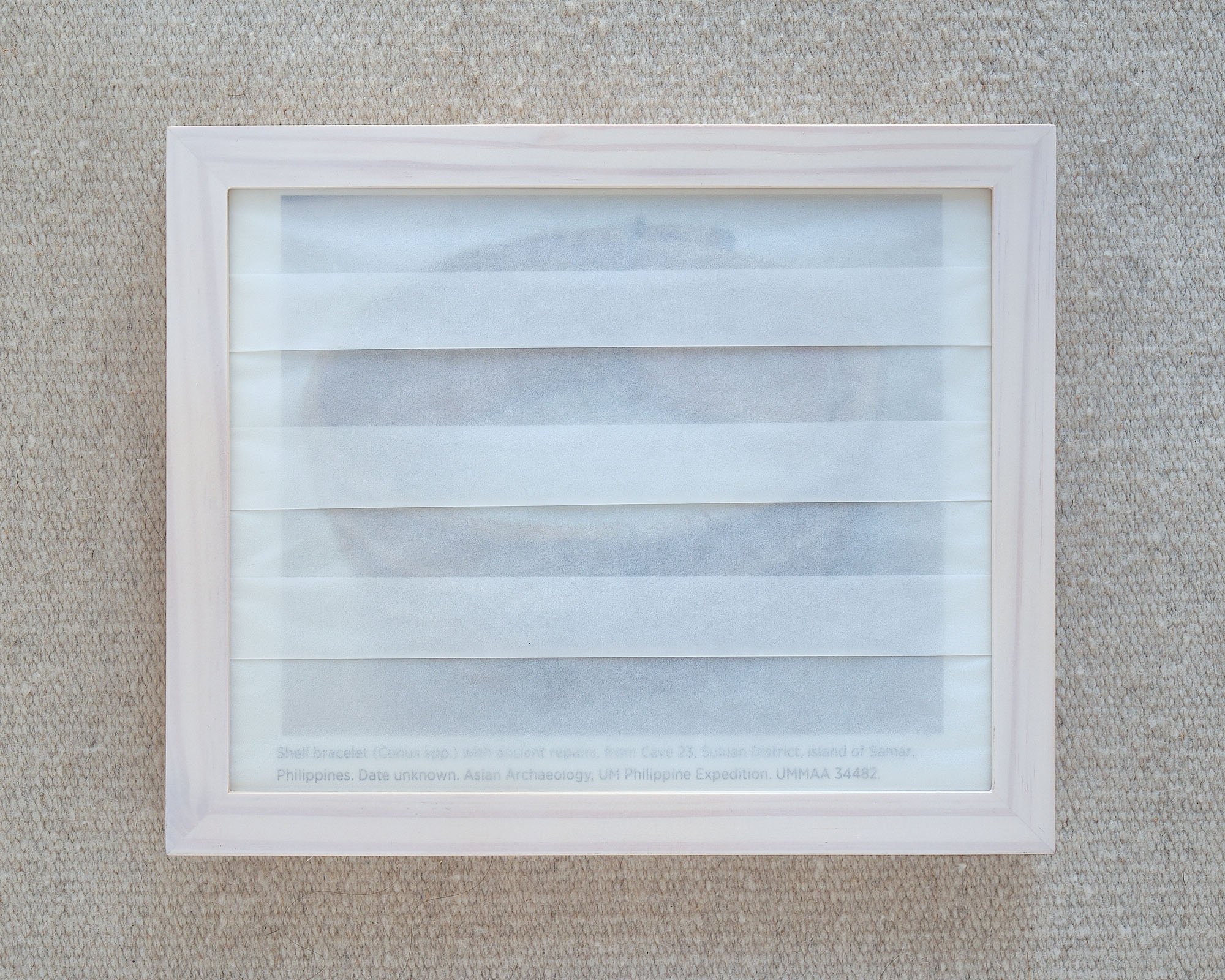

Phone pic from installation at The Contemporary Austin, 2021

Collecting & Packing

After collecting gifts, clothes, and basic household necessities that could take months to afford and buy, my parents would determine that they had enough to fill up a balikbayan box: a care package commonly used by the global Filipino/a/x diaspora to send goods, gifts, aide, and reminders of love to friends and family back in the Philippines. My mother would carefully, sometimes fancifully, gift wrap the items in decorative pleats and folds. Afterwards, my father would securely tape the bulging box, making every effort to ensure that it would safely make a successful journey to the Philippines.

Balikbayan is a Tagalog word—one of the at least 175 dialects spoken on the islands—that combines balik (“to return”) and bayan (“home country”). It is primarily used to describe the person returning home to the Philippines. Knowing this, I always thought it was funny to use it to describe the boxes themselves, because nothing my parents ever sent—not the DVDs of wild west films, not the French perfume bottles, not the Nintendo games—was originally from the the Philippines and now returning home.

Returning

In 2013, my parents began the process of moving back to the Philippines after almost thirty years of living and working in the United States. Rather than preparing a box of gifts for friends and family, they used balikbayan boxes to ship their own belongings. Watching them pack, I began to understand a deeper, melancholy truth to this practice: maybe they never wanted to leave. Economic insecurity pushed them to leave; economic success meant they could return.

Re-Imagining the balikbayan box

These experiences and memories of the balikbayan box serve as the basis for the creation of objects and images that can only resonate and find meaningful critique within an exhibition setting. I want to use this global yet intimate practice of Filipino/a/x families buying, collecting, and shipping objects (in my family’s case, from the United States to the Philippines) as a way to contrast and undo—if only imaginatively— the historic, violent, and dehumanizing colonial practices of extracting Indigenous cultural artifacts from the Philippines in order to ship them away, study and narrativize their meanings, and then paternalistically display them at museums in the United States.

Balikbayan box plinths

I will use balikbayan boxes to produce display structures after the manner of commonplace museum plinths. In the spirit of my father’s protective fastening of the boxes, I will tape together empty balikbayan boxes sourced from local balikbayan box shippers.

Each balikbayan box plinth will remain fully closed using layers of white artist tape (instead of my dad’s packing tape), acting as a recognizable but now surreptitious object within the usual structures of any exhibition. No objects will be placed on the plinths. I’m interested in discovering to what extent I can transform a structure that promotes seeing into an object that denies it.

Viewers can only guess at the possibility of clearly seeing—and therefore claiming to know—the objects and artifacts that are potentially safely inside the boxes; they have been seen and studied enough.

Wrapped Photographic prints

In addition to the plinths, I will also create photographic prints wrapped in—and obscured by—the typical archival papers used on delicate objects in storage. I will reappropriate these protective papers as gift wrappings, decoratively folding and pleating each sheet over the photographs in honor of my mother’s memorable skills.

The photo prints will be screenshots sourced from the University of Michigan’s Museum of Anthropological Archaeology, which stores over 15,000 Indigenous objects from burial sites in the Philippine islands—including human remains—taken during a period of colonial excavation (1922-1925) and “gifted” to the museum by archaeologist Carl E. Guthe.

Exhibition Proposal

By positioning a diasporic Filipino/a/x practice of care, kinship, and return as a familiar—but now fugitive—object within exhibition spaces, I’m interested in presenting these boxes as containers of an imaginary space, one where viewers might collectively think about and feel the loss of these taken objects, and then envision their extralegal return in a process whereby my parents, my aunties and uncles and cousins, my brother and I, all Filipino/a/xs in the United States, take these objects up in our hands, lovingly wrap them, safely put them in those empty boxes, and finally return them to the home country.

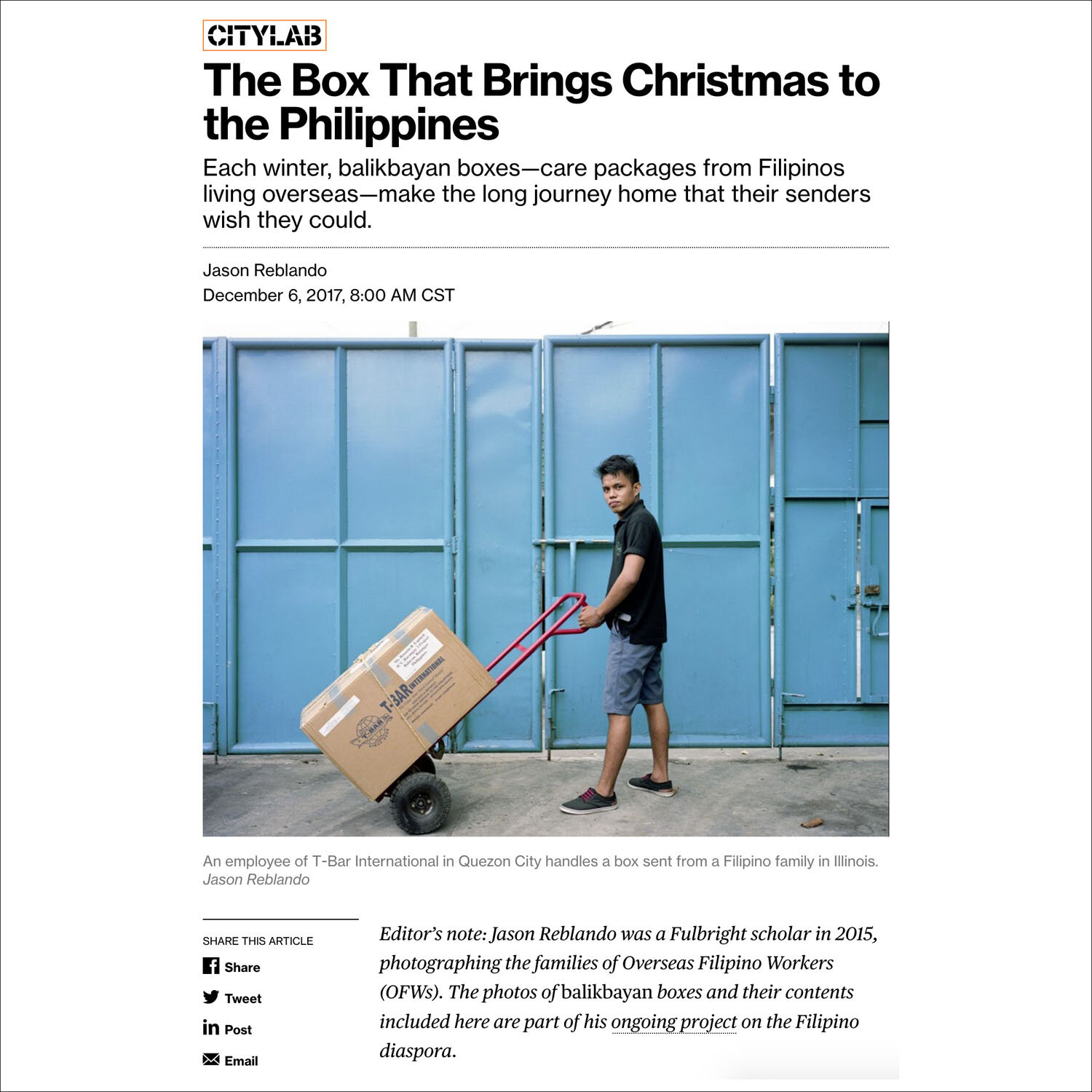

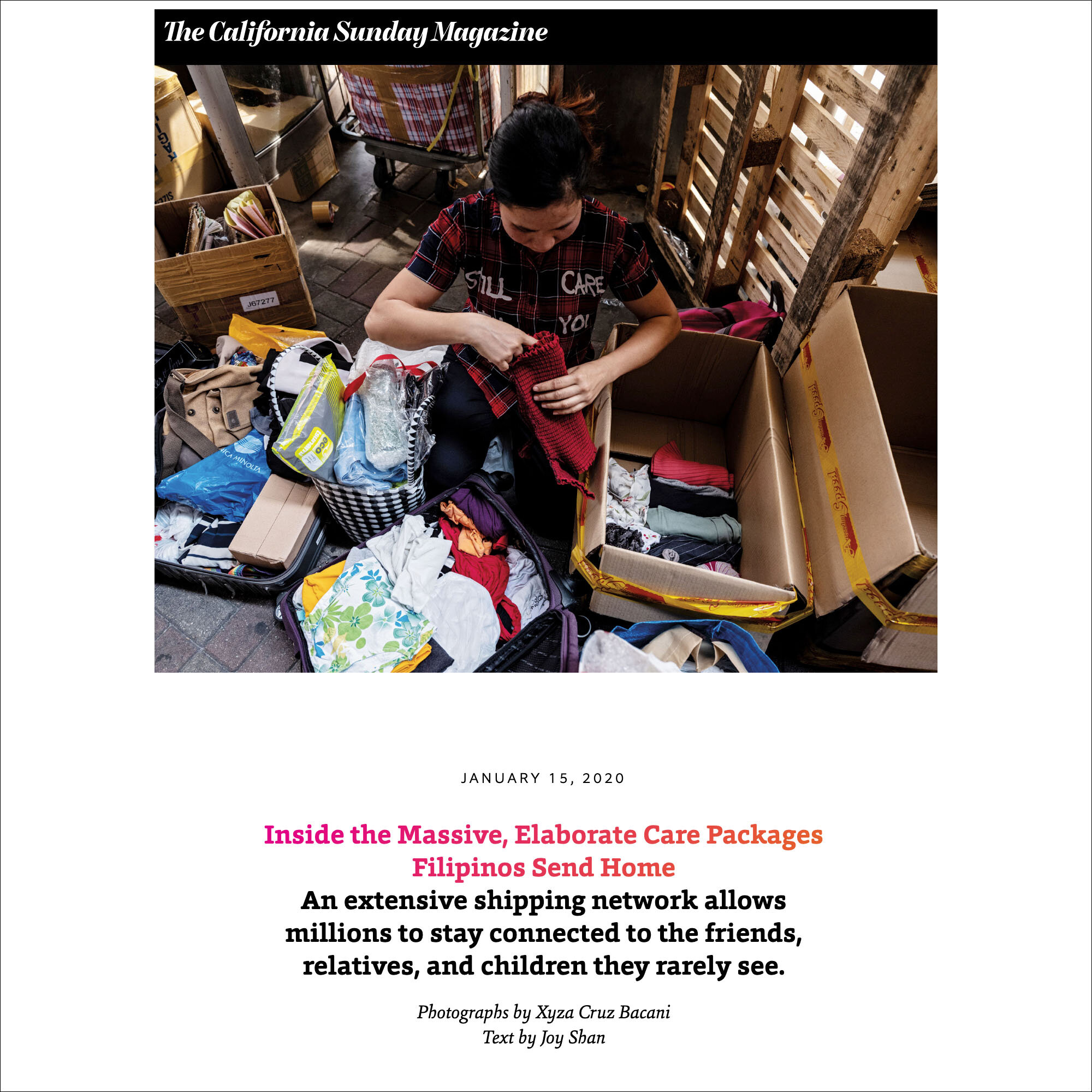

Popular press about balikbayan boxes

Clicking on a slideshow image will send you to the referenced article.

some of the many Global shippers

Clicking on a slideshow image will send you to that shipper’s website.

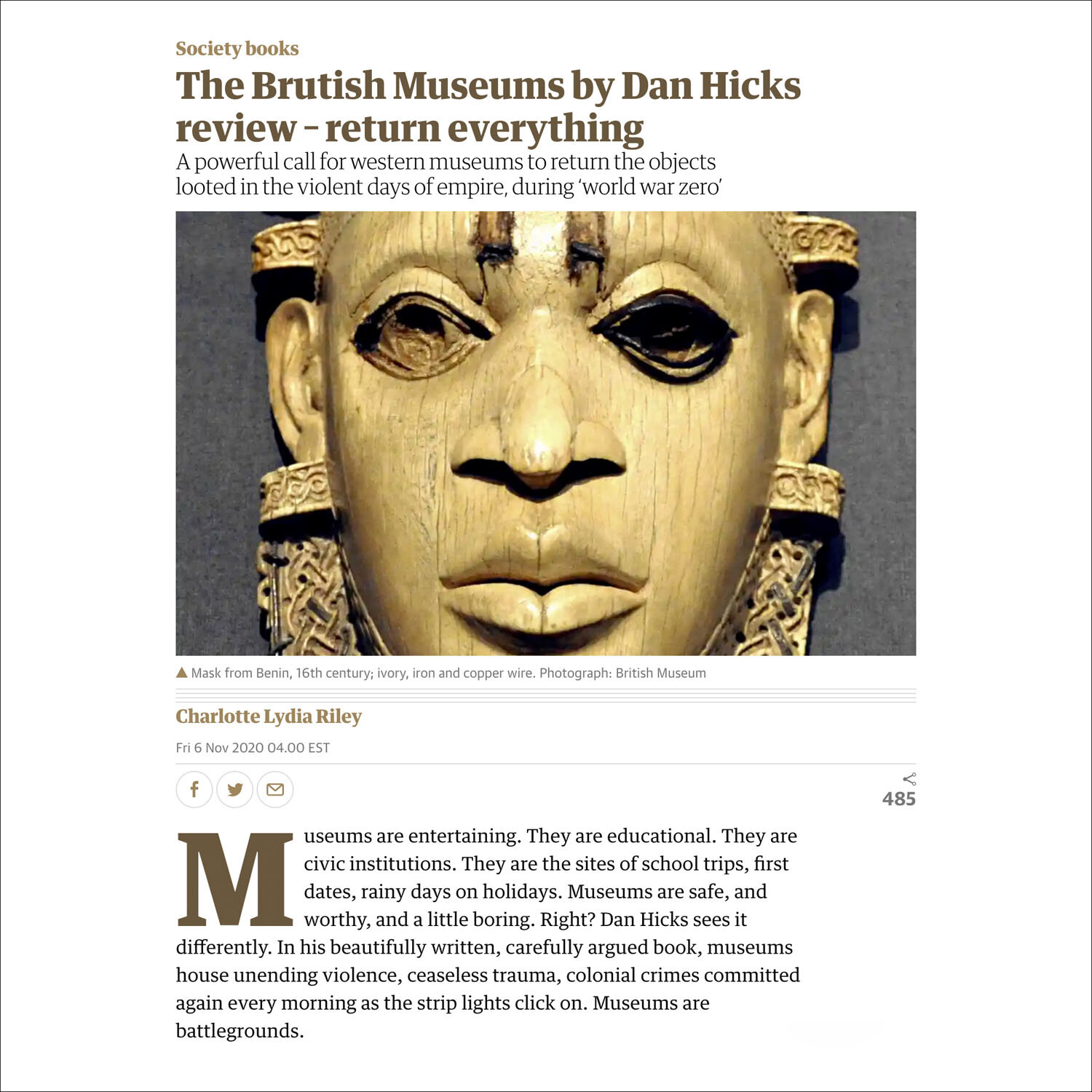

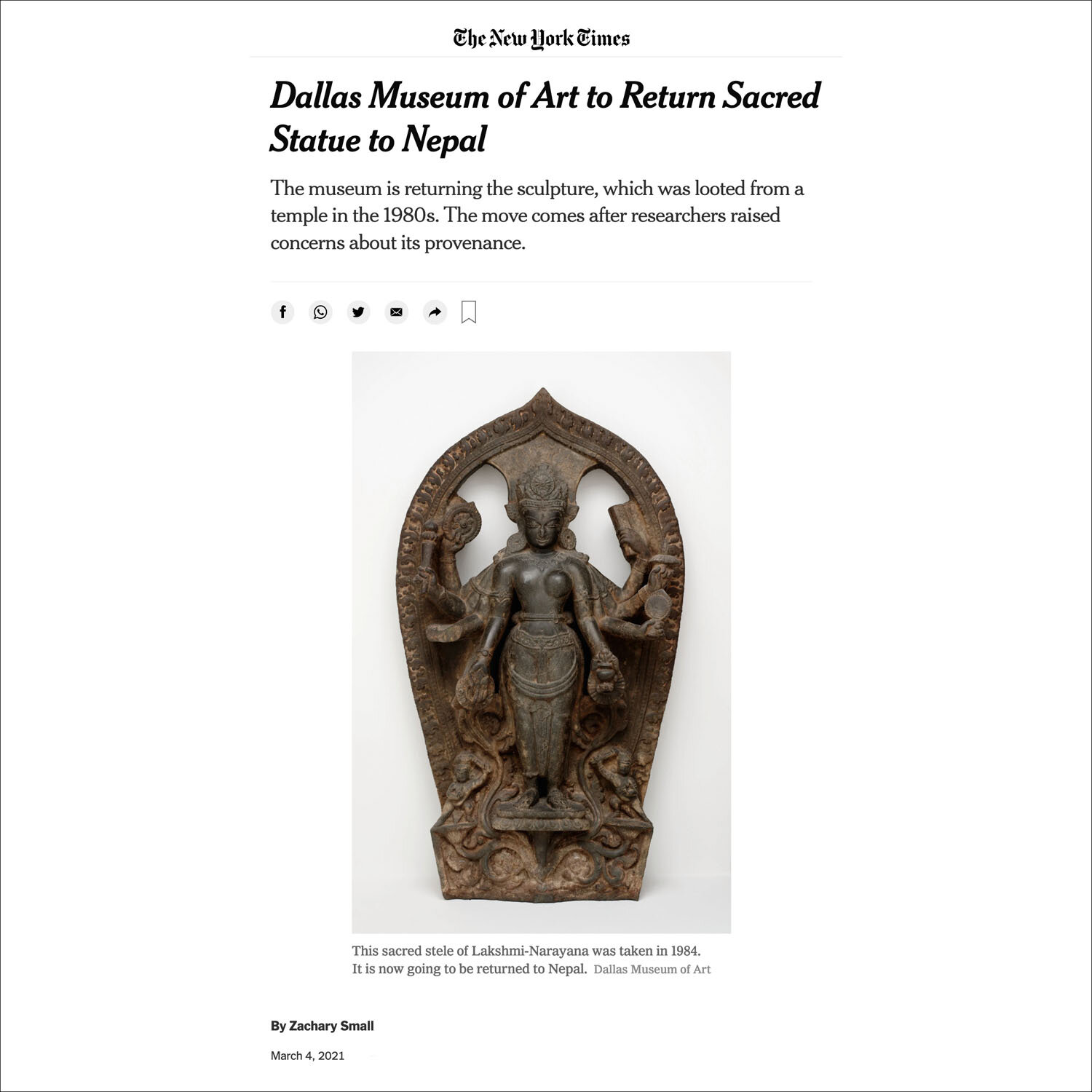

Articles about Museums, cultural artifacts, and issues of restitution

Clicking on a slideshow image will send you to the referenced article.

Scholarly Project Documenting Artifact Collections outside the Philippines

Clicking on image will send you to the project.

Collections of Indigenous Philippine artifacts in the United States

Museum of Anthropological Archaeology University of Michigan

“From 1922 to 1925, Carl E. Guthe, the founding director of the Museum, led its first overseas expedition in the Philippines (then a U.S. colony). Over three years, Guthe excavated more than 450 sites throughout the southern Philippines. Most were burial sites, dating from the 14th through 17th century AD. The Philippine Expedition Collection of more than 15,000 objects includes local and imported ceramics, ornaments, and metal objects, as well as human remains. Recent research on the collection by scholars from the U.S., Philippines, China, and elsewhere continues to add new knowledge to the study of the Southeast Asian past. This marine shell bracelet was recovered in excavations of a larger burial cave on the island of Samar in the southern Philippines. Ancient repairs show that it was valued by its owner.”

Frank Murphy Memorial Museum

Harbor Beach, Michigan

“In 1933, FDR offered Frank the position of Governor General of the Philippines and tasked him with the responsibility of leading that country from U.S. colonial status to independence. While there, Frank and his family purchased or were gifted many items which are now displayed as part of the museum’s Philippine Cultural Collection. ”

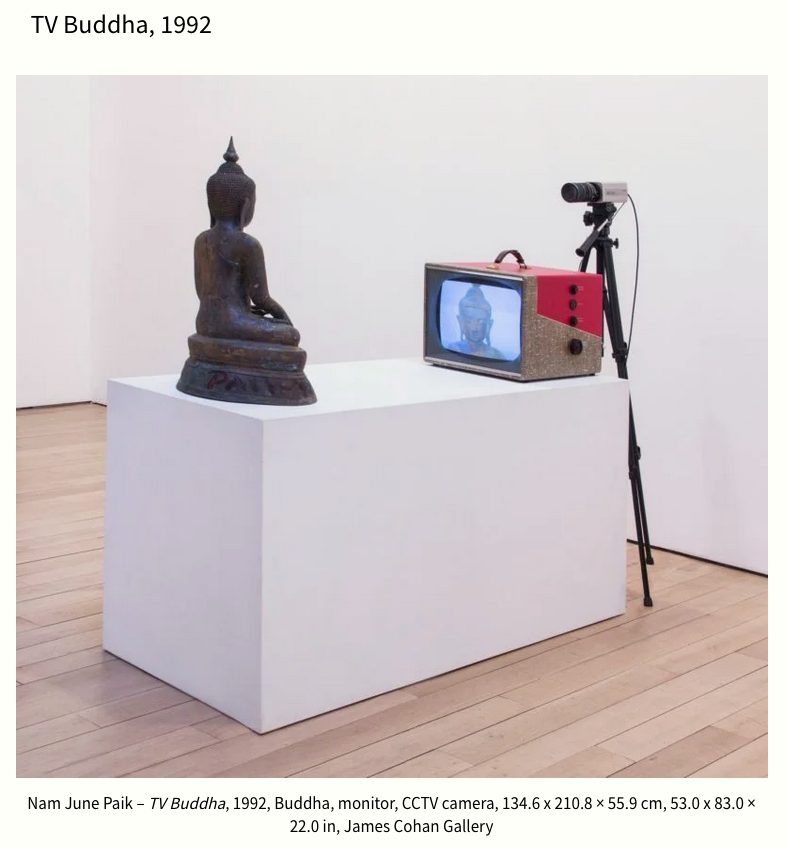

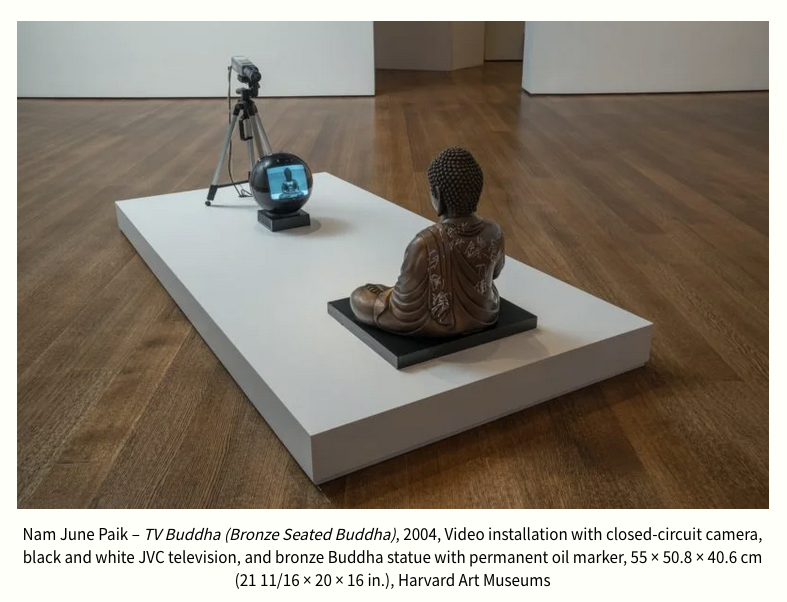

Visual Notes & References

Artist Nam June Paik

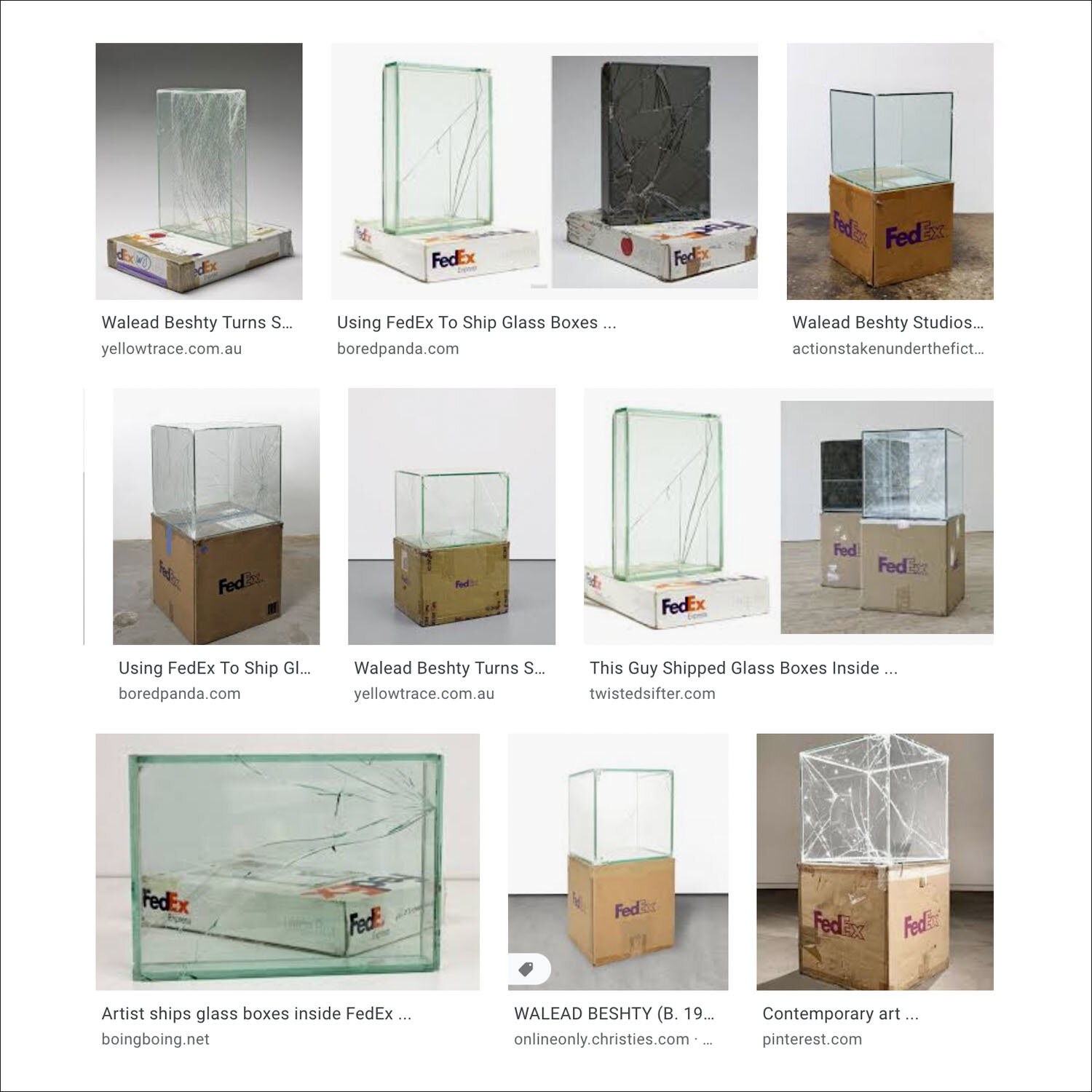

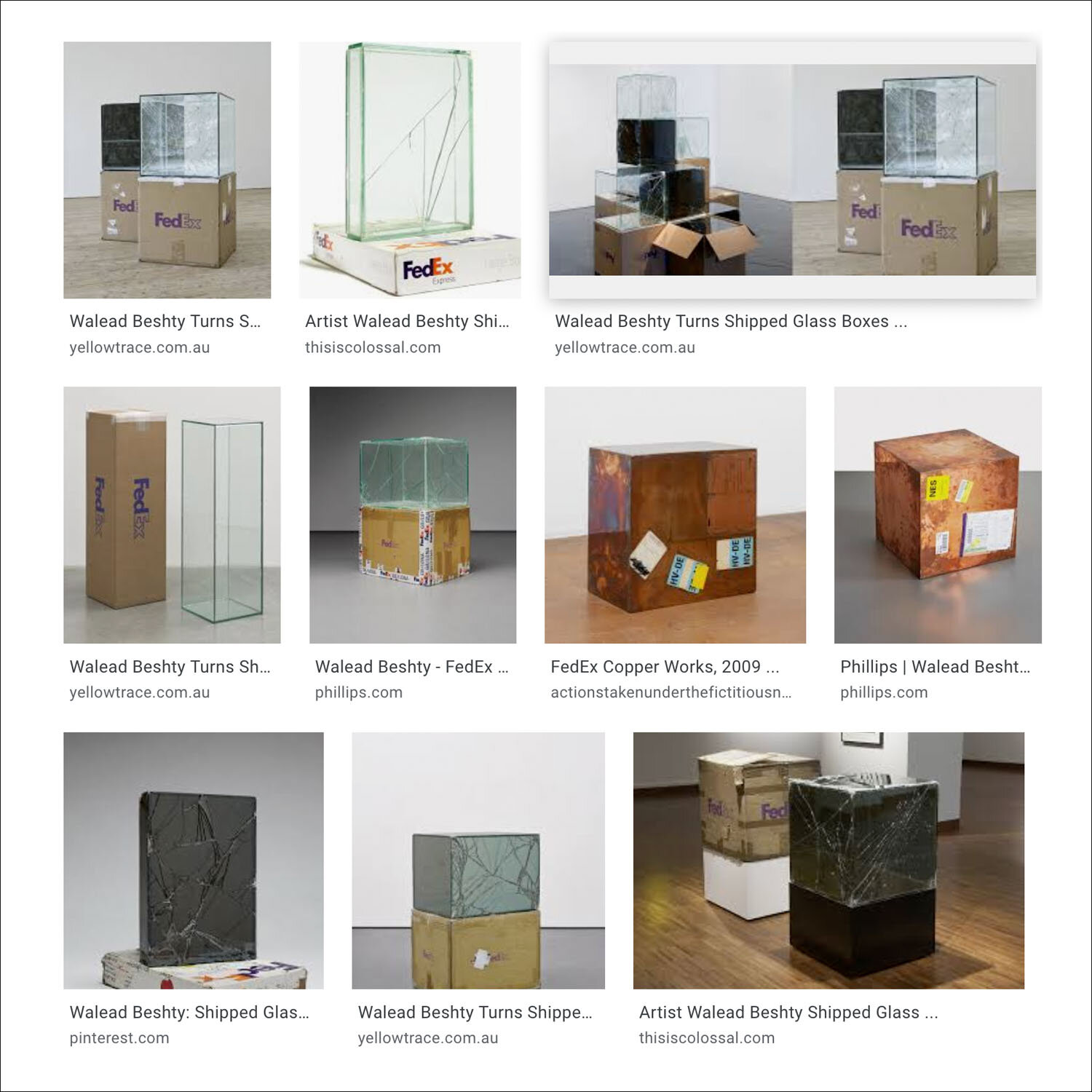

Artist Walead Beshty

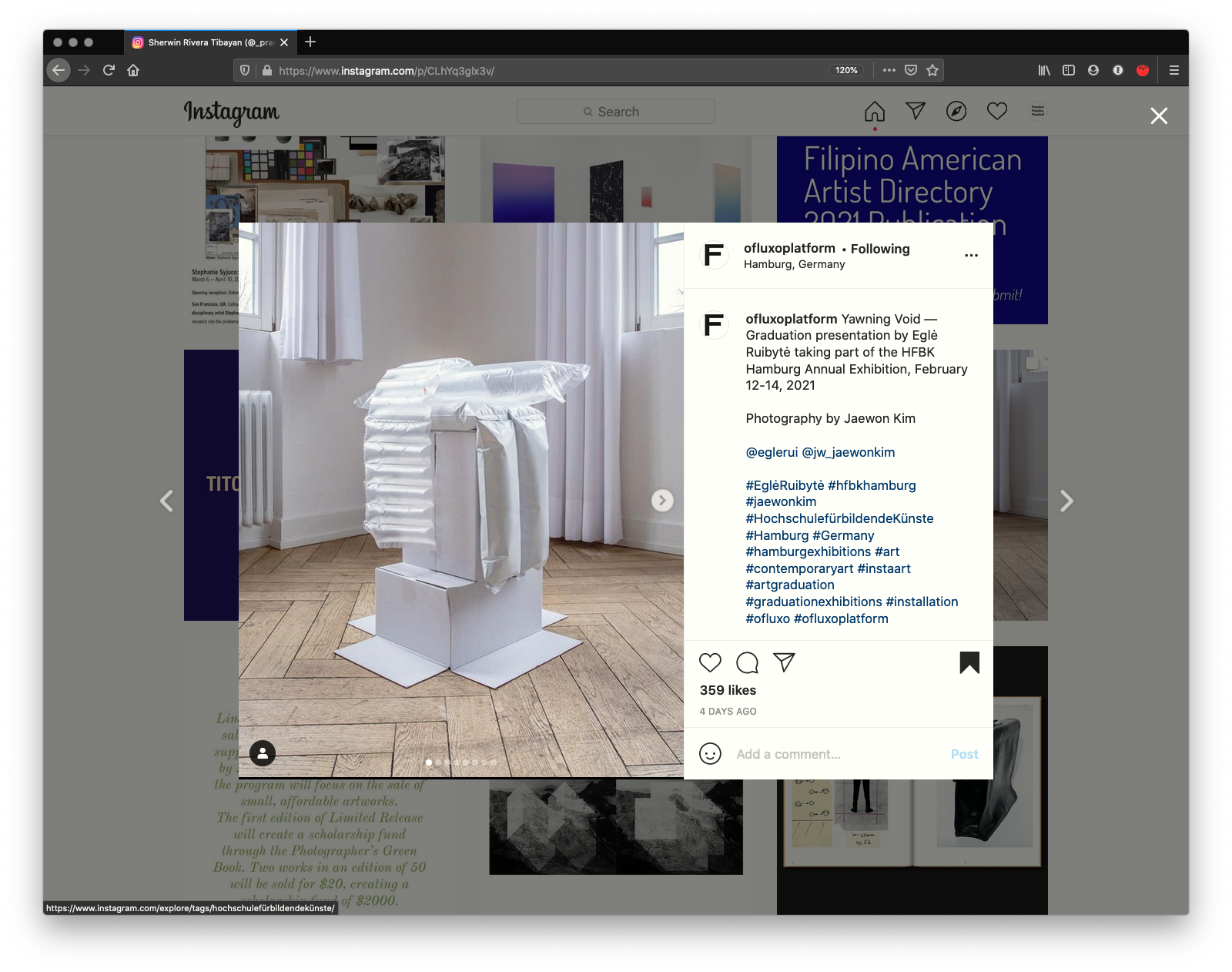

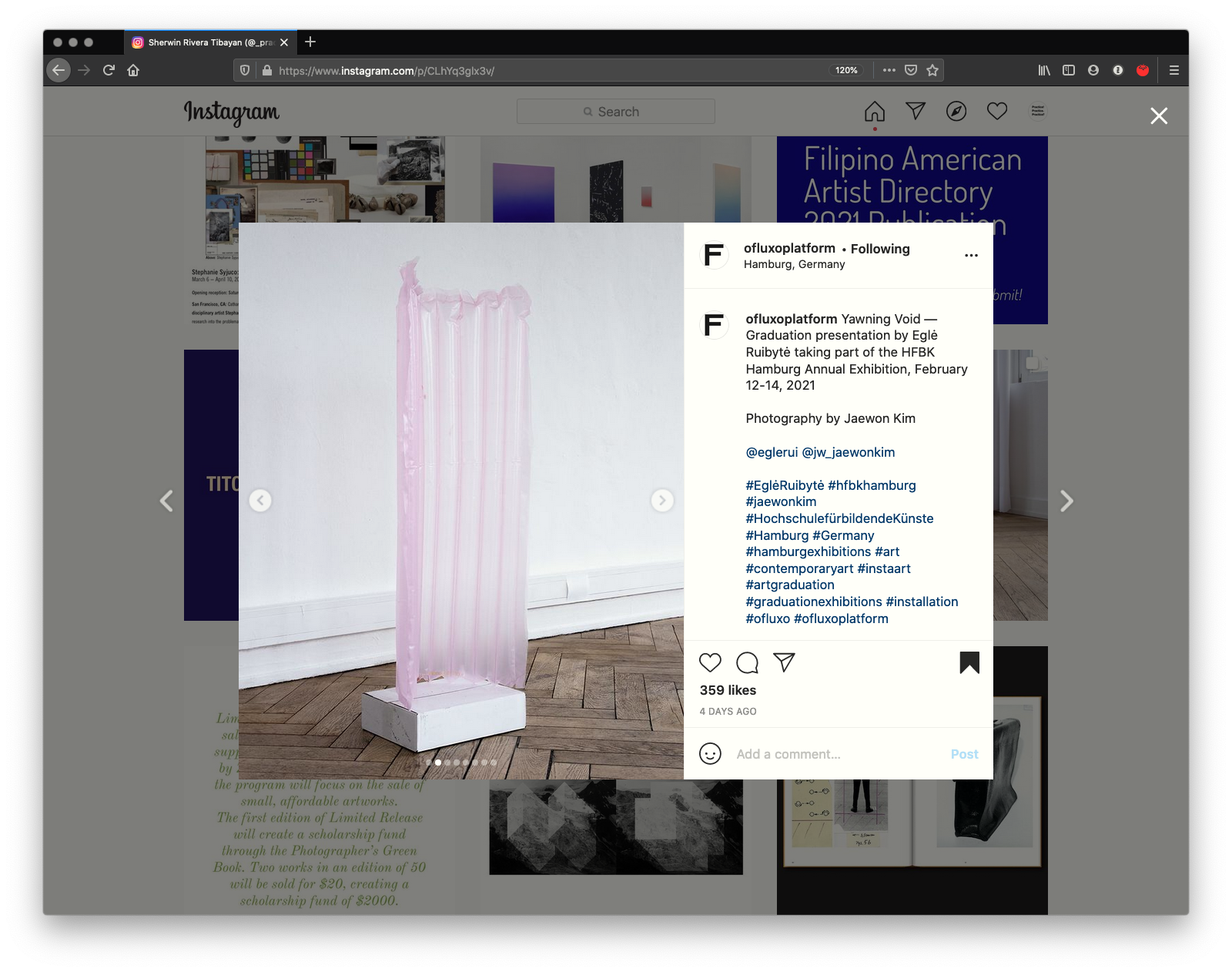

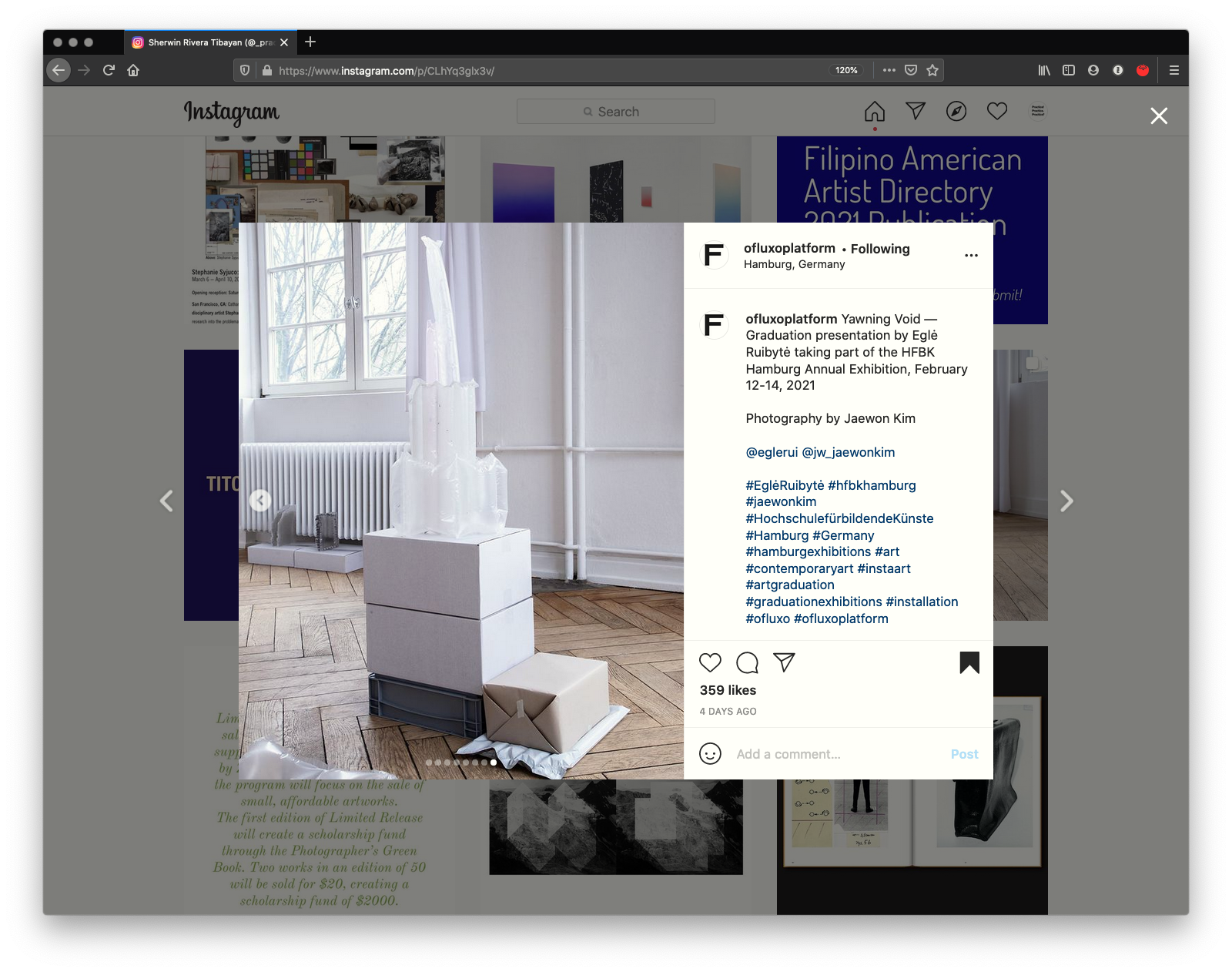

Artist Egle Ruibyte