Is Filipino American Navy a personal project in public relations? If not, why not? If yes, so what?

Within this project, I operate in parallel tracks of identity and mixed feelings in an attempt to draw out the ways in which photographic images have shaped, and may continue to shape, Filipino American claims to participation, presence, and dignity in the United States.

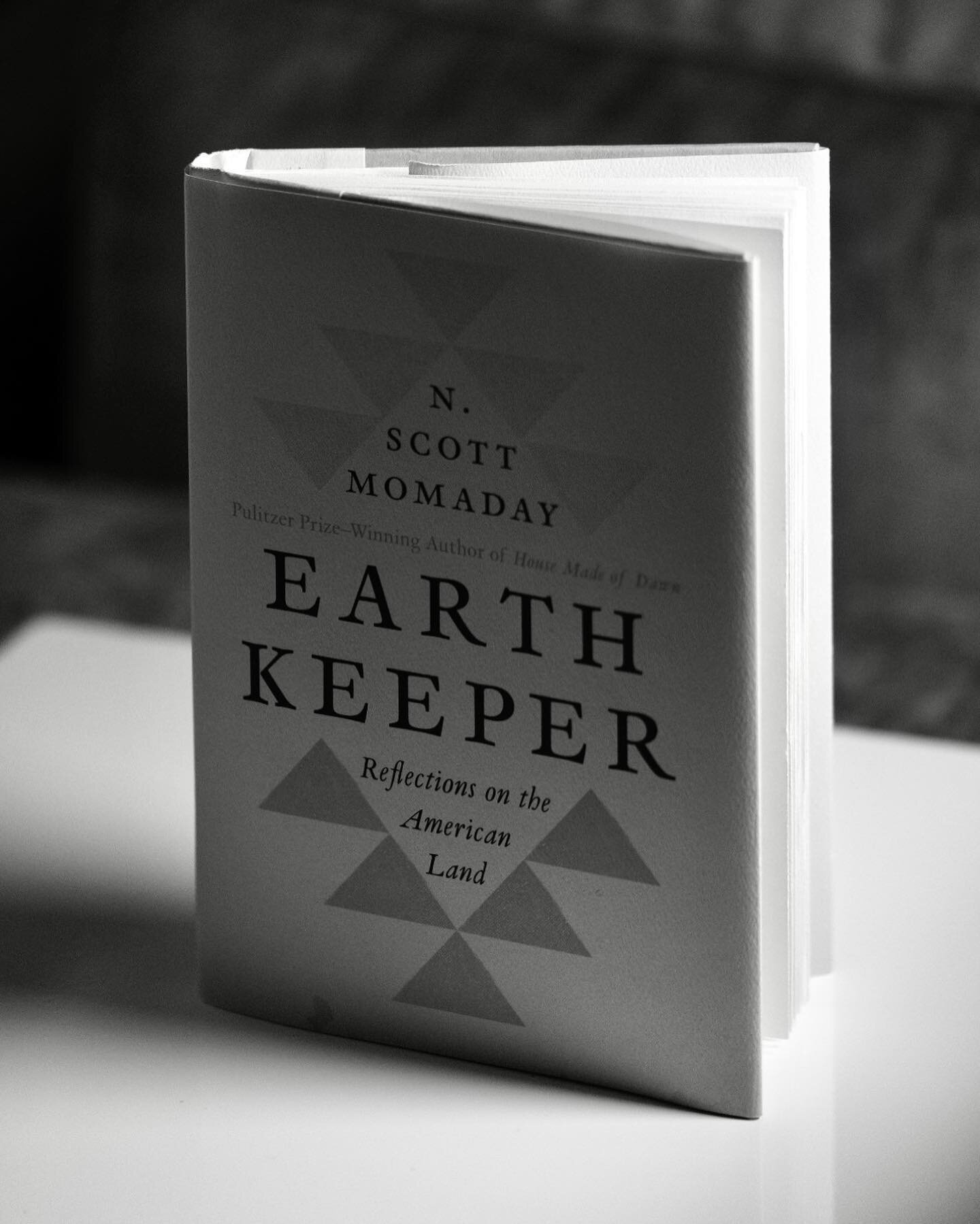

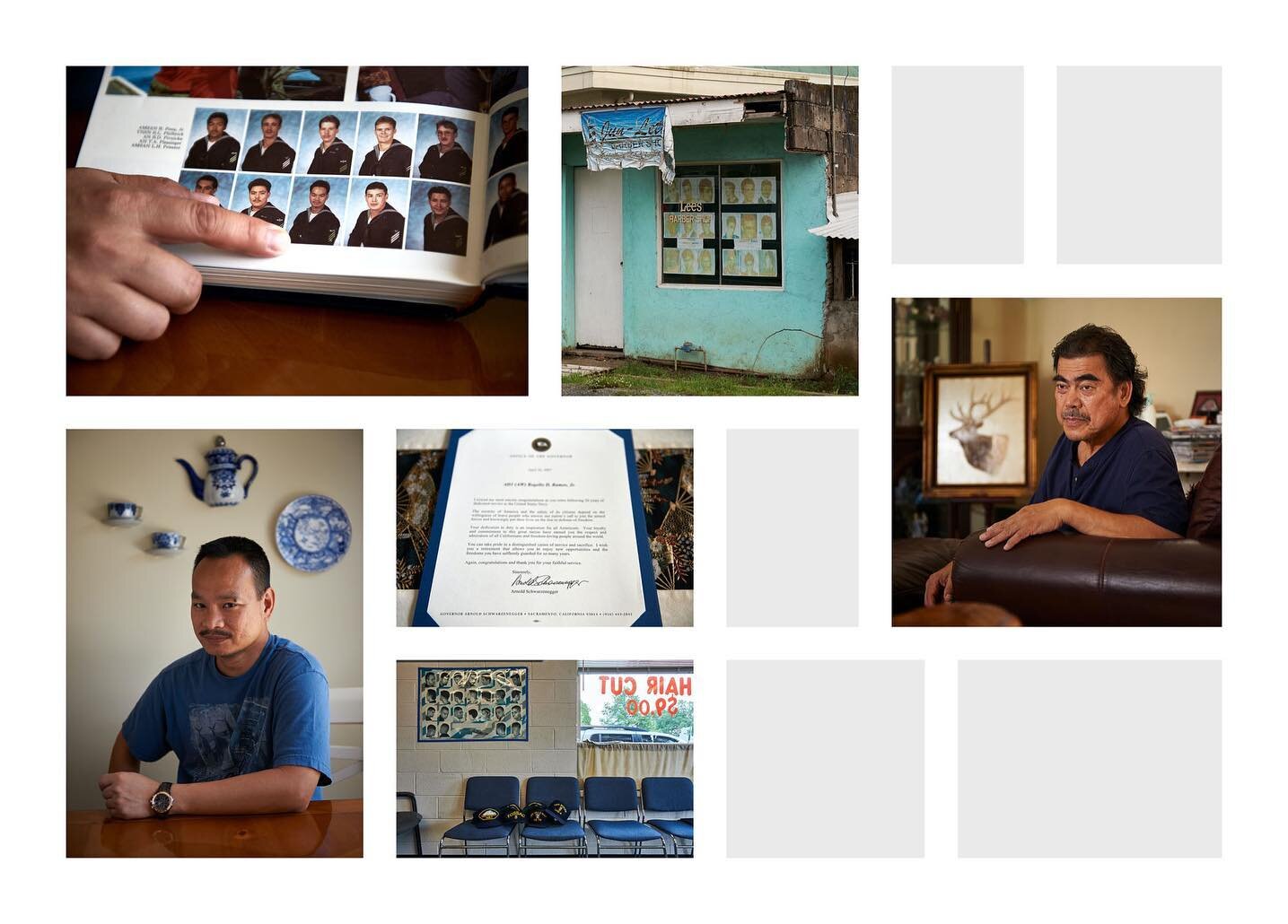

As a son and brother to two people who served in the U.S. Navy, I’m interested in exploring how the conventions and expectations of formal photographic portraiture frame ideas of dignity and status. I’d like to discover to what extent associations with military service in particular provide significant, additional, and legitimizing claims to national belonging. Does a picture of my father or brother in uniform make them more understandable and readable as Americans?

As a naturalized citizen who was born on a U.S. military base in the Philippines—one that no longer exists—I’m interested in how Filipino American military families share and display the possessions of their documented past, both the formal and casual photography as well as the paperwork and memorabilia, to reflect and tell their stories within private, domestic spaces. I wonder in what ways these documents and objects and arrangements drift away from embodiments of personal and familial pride, and towards mere evidence in the eyes of visitors like myself. Does the intervention of my photography reflect ideas of pride and agency and self-determination, or am I only using the content of these pictures as bulwarks against discrimination and prejudice from potential audiences?

As a thirty-eight year old Filipino American arguably in the middle of my working life, I’m interested in experiencing how invitations to make pictures of domestic spaces, largely by retired career military families, furnishes specific ideas about accumulated material and financial success. I wonder to what extent these invitations might lead to further conversations about personal aspirations, dreams and ideas of home and security, and idiosyncratic and generational visions of America.

As a visual artist working within the traditions, technologies, and discourses of documentary photography, I’m interested in asking—and worried about the answer to—two questions. First, if I can make it visible, will that make it legible? And second, if what I’ve made is legible, who am I asking to do the work of looking, reflecting, and understanding?

I would like to compare and contrast these four tracks of identity and indecision with the making and recording of portraits and domestic encounters with Filipino Americans, their objects and manners of display. Further, I would like consider these efforts with and against larger historical and institutional modes of preservation and presentation, especially as they relate to postcolonial understandings of the imperial museum and archives, two linked structures that continually signify the simultaneous accumulation and dispossession of indigenous Filipino artifacts and materials in the United States.

In the photographic process of taking, making, accumulating, and sorting, will I find strategies and contexts and genuine ways to resist—or will I inadvertently reinforce—the very processes of knowledge production and display that have historically reduced Filipino Americans, and Asian American generally, to an observable type?