Current Readings: 17 August 2020

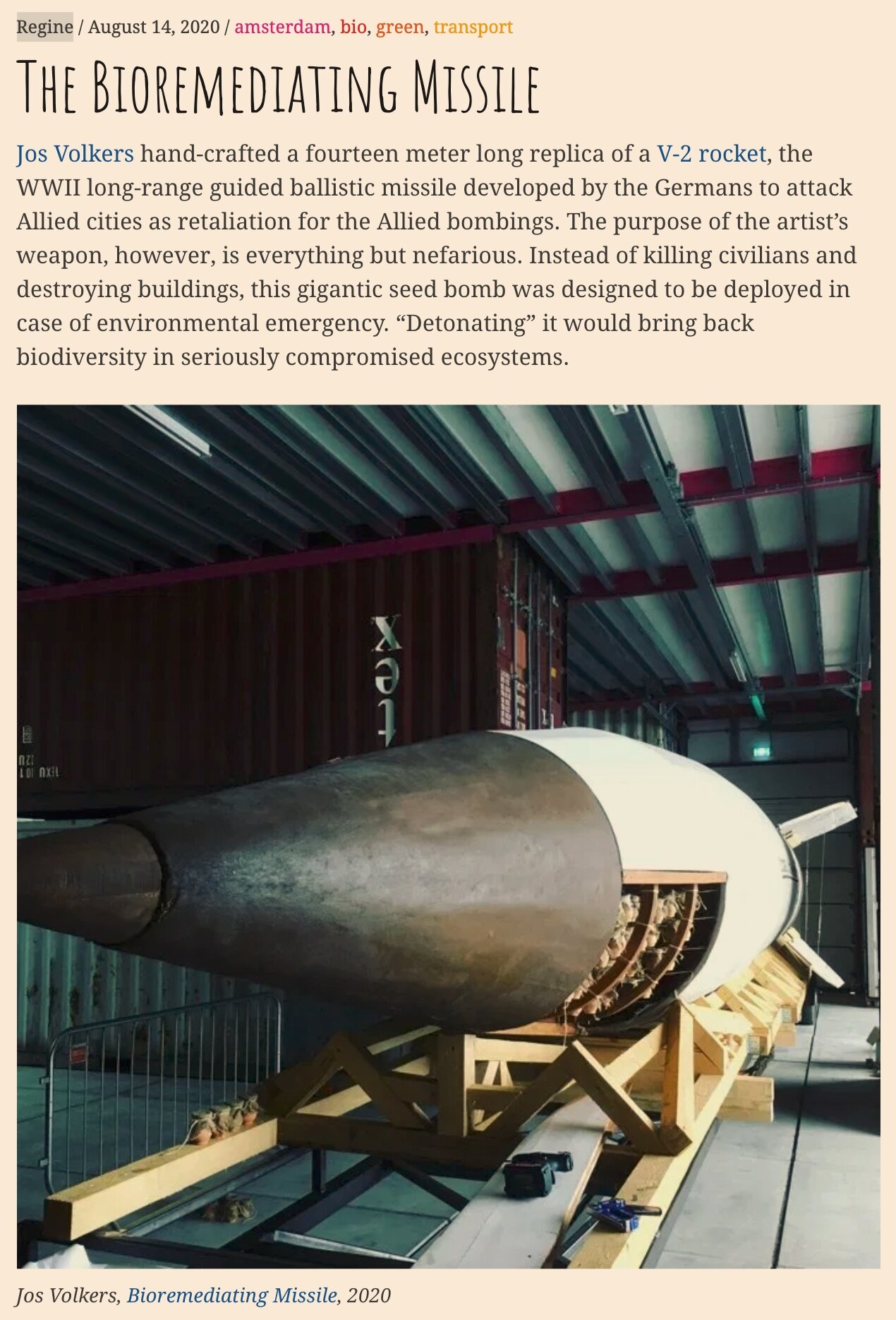

Christine Sun Kim: 2019 Whitney Biennial

Took these four pictures when I was in NYC last year and caught the 2019 Whitney Biennial (I think there were six total prints, however). These works by Christine Sun Kim were new to me, and my favorite encounter from the exhibition. Below is a short interview with the artist and her work and processes.

Article via The New York Times Magazine

Artist Website: Christine Sun Kim

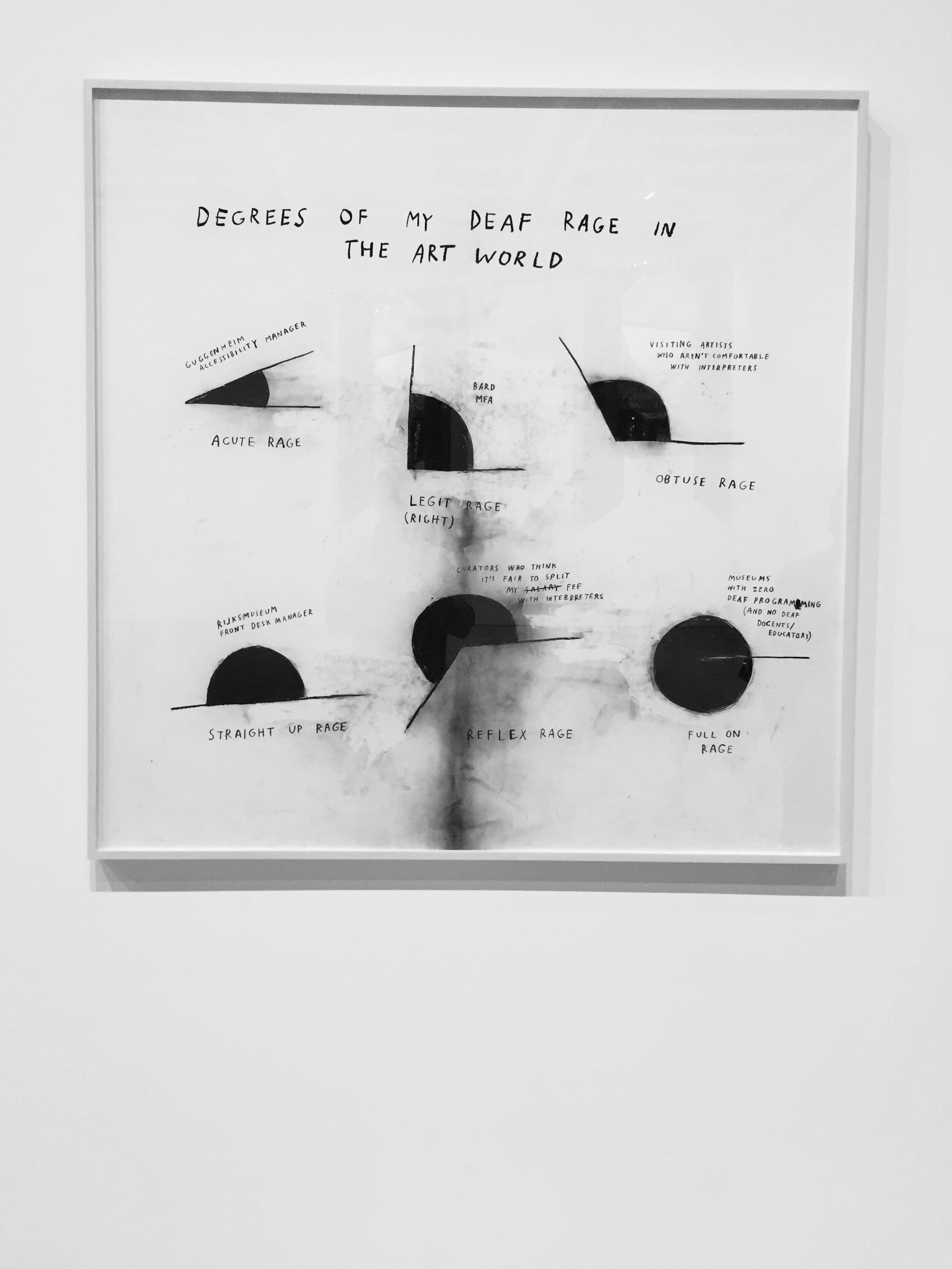

Filipino American Artist and Art Community Manifesto

““During the past month, we’ve been working on a collaborative writing exercise to develop a collective manifesto for the directory. We hope that this piece will help to uplift and give you strength and power to move forward as it has for us.

Maraming salamat to all the artists who contributed to this writing, named and anonymous “”

The Endless Doomscroller

Current Desktop: 12 August 2020

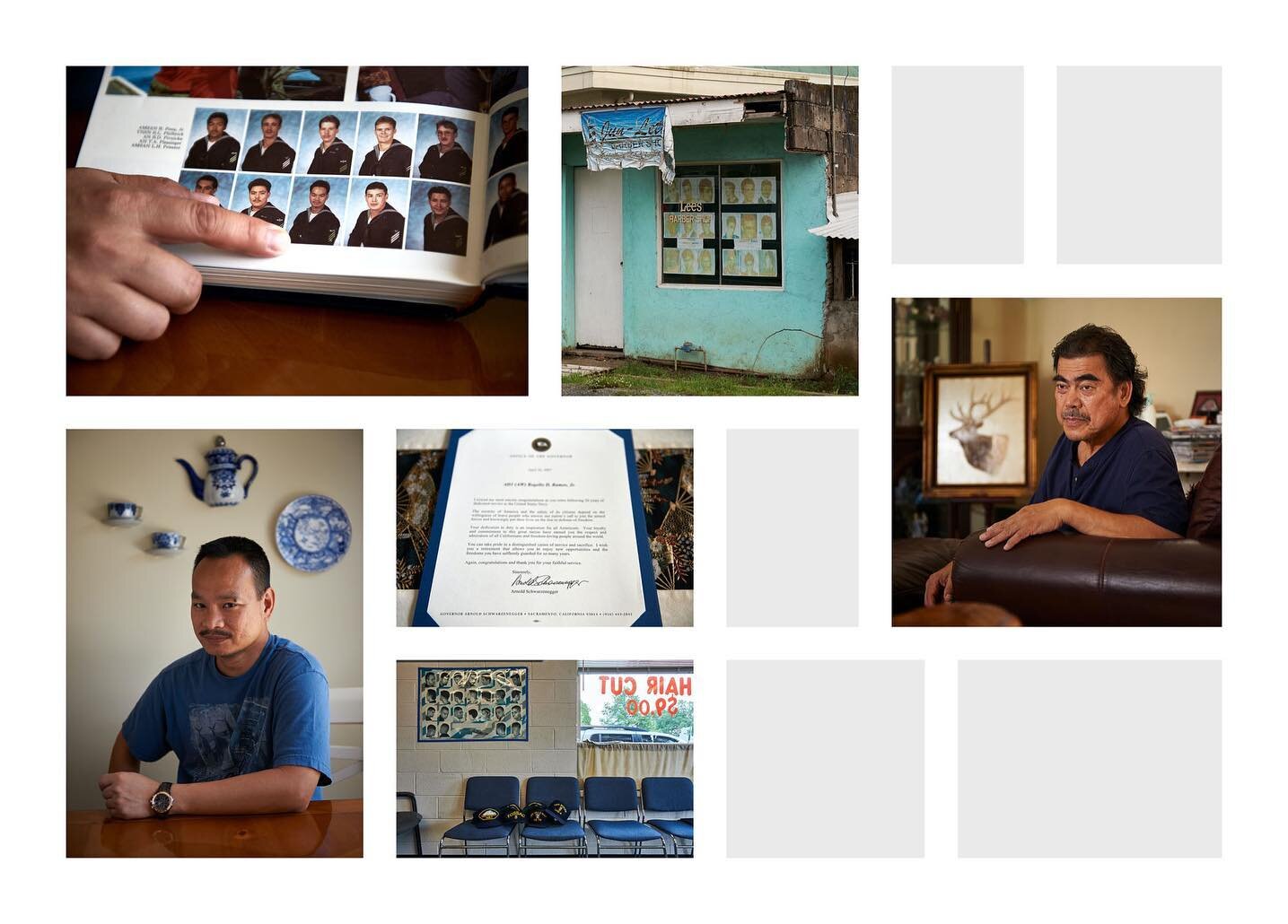

Possible directions, possible concerns for FilAm Navy Project

Is Filipino American Navy a personal project in public relations? If not, why not? If yes, so what?

Within this project, I operate in parallel tracks of identity and mixed feelings in an attempt to draw out the ways in which photographic images have shaped, and may continue to shape, Filipino American claims to participation, presence, and dignity in the United States.

As a son and brother to two people who served in the U.S. Navy, I’m interested in exploring how the conventions and expectations of formal photographic portraiture frame ideas of dignity and status. I’d like to discover to what extent associations with military service in particular provide significant, additional, and legitimizing claims to national belonging. Does a picture of my father or brother in uniform make them more understandable and readable as Americans?

As a naturalized citizen who was born on a U.S. military base in the Philippines—one that no longer exists—I’m interested in how Filipino American military families share and display the possessions of their documented past, both the formal and casual photography as well as the paperwork and memorabilia, to reflect and tell their stories within private, domestic spaces. I wonder in what ways these documents and objects and arrangements drift away from embodiments of personal and familial pride, and towards mere evidence in the eyes of visitors like myself. Does the intervention of my photography reflect ideas of pride and agency and self-determination, or am I only using the content of these pictures as bulwarks against discrimination and prejudice from potential audiences?

As a thirty-eight year old Filipino American arguably in the middle of my working life, I’m interested in experiencing how invitations to make pictures of domestic spaces, largely by retired career military families, furnishes specific ideas about accumulated material and financial success. I wonder to what extent these invitations might lead to further conversations about personal aspirations, dreams and ideas of home and security, and idiosyncratic and generational visions of America.

As a visual artist working within the traditions, technologies, and discourses of documentary photography, I’m interested in asking—and worried about the answer to—two questions. First, if I can make it visible, will that make it legible? And second, if what I’ve made is legible, who am I asking to do the work of looking, reflecting, and understanding?

I would like to compare and contrast these four tracks of identity and indecision with the making and recording of portraits and domestic encounters with Filipino Americans, their objects and manners of display. Further, I would like consider these efforts with and against larger historical and institutional modes of preservation and presentation, especially as they relate to postcolonial understandings of the imperial museum and archives, two linked structures that continually signify the simultaneous accumulation and dispossession of indigenous Filipino artifacts and materials in the United States.

In the photographic process of taking, making, accumulating, and sorting, will I find strategies and contexts and genuine ways to resist—or will I inadvertently reinforce—the very processes of knowledge production and display that have historically reduced Filipino Americans, and Asian American generally, to an observable type?

Alternative Canons Resource Page from Strange Fire Collective

“The field of writing on the topic of photography and visual culture is constantly expanding, and yet there is a rigidly established canon of literature that remains a consistent source of assignments in the classroom. The purpose of this guide is to provide further and alternative readings. Though the canonical texts remain relevant and important, this guide contains literature that addresses similar themes, providing an opportunity to address contemporary engagement with these ideas.”

Zadie Smith on timelessness and universality

“As writers and readers and critics, we English remain terribly proud of our conservative tastes. Every year the polls tell us ‘Middlemarch’ is the country’s favorite novel, followed by ‘Pride and Prejudice’, followed by ‘Jane Eyre’ (sometime this order is reversed). Oh, the universality of the themes. Oh, the timelessness of the prose. But there is a misunderstanding, in England, about the words universality and timelessness as they relate to our canon. What is universal and timeless in literature is need—we continue to need novelists wo seem to know and feel, and who move between these two modes of operation with wondrous fluidity. What is not universal or temples, though, is form.”

From Zadie Smith’s 2009 book of essays, Changing My Mind

Frederick Douglass, photography, and the image of dignity

“He wrote essays on the photograph and its majesty, posed for hundreds of different portraits, many of them endlessly copied and distributed around the United States. He was a theorist of the technology and a student of its social impact, one of the first to consider the fixed image as a public relations instrument. Indeed, the determined abolitionist believed fervently that he could represent the dignity of his race, inspiring others, and expanding the visual vocabulary of mass culture. ”

via The New Republic